Image from Pixabay

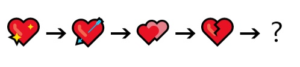

Men and women are attracted to each another because they are made that way—this is not an attraction that needs to be learned! What we do need to learn in our post-Eden world is how to channel our desires in a productive and wholesome way. In order to experience romantic love as it was intended to be—as God intended it to be—moving away from sin and towards God is a move in the right direction. Since God created sex, romance, and love, His advice to us is worth heeding. His prescription for all broken relationships in this fallen world can be summarized in the words “unconditional love.”

But does the commandment to “love your neighbor” apply to the realm of dating? Or would that be reading too much into this commandment? Jesus was once asked by an expert in the law to define who his neighbor was (Luke 10:29b). Jesus responded with the Parable of the Good Samaritan, who was an unexpected friend to someone who had fallen victim to robbers. Tellingly, Luke records that the expert in the law asked Jesus this question in order to justify himself (Luke 10:29a). So it is with human nature. Left to our own devices, we avoid loving people unless it suits our purposes. Jesus, however, did not embrace a narrow understanding of the word “neighbor” but rather a broad one. In fact, he went so far as to say that we should love our enemies (Matthew 5:44, Luke 6:27)—how much more, then, should we love those we call our lovers? Regardless of whether we care to accept it, there is no exception to the Golden Rule when romance is involved.

Tired of the dominant dating culture? (You know, where people are considered disposable.)

Tired of the dominant dating culture? (You know, where people are considered disposable.)